Battle of Angaur

| Battle of Angaur | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Mariana and Palau Islands campaign of the Pacific Theater (World War II) | |||||||

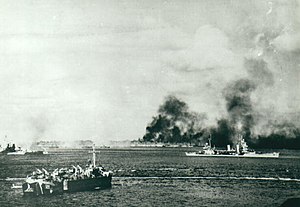

U.S. naval bombardment of Angaur, c. 15 September 1944. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Paul J. Mueller |

Ushio Goto † Sadae Inoue | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 10,000 | 1,400[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

264 killed 1,354 wounded[1] |

1,350 killed 50 captured[1] | ||||||

The Battle of Angaur was a major battle of the Pacific campaign in World War II, fought on the island of Angaur in the Palau Islands from 17 September to 22 October 1944. This battle was part of a larger offensive campaign known as Operation Forager which ran from June to November 1944 in the Pacific Theater of Operations, and Operation Stalemate II in particular.

Background

[edit]Angaur is a small coral island, just 3 mi (4.8 km) long, separated from Peleliu by a 7 mi (11 km) wide strait, from which phosphate was mined.[2] In mid-1944, the Japanese had 1,400 troops on the island, under the overall command of Palau Sector Group commander Lieutenant General Sadae Inoue and under the direct command of Major Ushio Goto who was stationed on the island.[3]

The weak defenses of the Palaus and the potential for airfield construction made them attractive targets for the Americans after the capture of the Marshall Islands, but a shortage of landing craft meant that operations against the Palaus could not begin until the Mariana Islands were secure.

Once the assault on Peleliu was "well in hand", the 322nd Regimental combat team (RCT) would land on the northern Beach Red, and the 321st RCT on the eastern Beach Blue. Both teams were part of the 81st Infantry Division, commanded by Major General Paul J. Mueller.[4] The Japanese defending both Peleliu and Angaur, were the combat-hardened men of the 14th Infantry Division with four years of experience fighting in Manchuria behind them, and personally sent to defend the Palaus by Prime Minister Hideki Tojo. The 1,400 soldiers garrisoned on Angaur were the 1st Battalion, 59th Infantry Regiment.

Battle

[edit]

Bombardment of Angaur by the battleship Tennessee, four cruisers, and 40 Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bombers from the aircraft carrier Wasp began on 11 September 1944. Six days later on 17 September, the two RCTs landed on the northeast and southeast coasts. Not having enough troops to defend all the beaches, Goto selected the most attractive beach (code named Green Beach by the Americans) for an amphibious landing to build his beach defenses. His defenses consisted of a formidable array of pillboxes, blockhouses, trenches and antitank ditches. Seeing the buildup around Green Beach, Mueller decided to land his troops at the more constricted but less defended beaches of Red and Blue Beach. The 322nd RCT received sporadic mortar and machine gun fire, but they landed fairly unopposed and with light casualties. The 321st landing at Blue Beach faced heavier machine gun and mortar fire, but it too was able to get ashore with minimal casualties.[5]

Unbeknownst to them, this was all part of the Japanese new "defense in depth strategy" that they would face, along with the 1st Marine Division on nearby Peleliu. The Japanese strategy had been modified to allow the Americans to land rather unopposed and move inward, with "in depth" defensive lines further inland, and initiating nighttime counterattacks en masse while the Americans were still heavily congregated on the beachheads, attempting to drive them back into the sea. Suicidal banzai charges as seen on Tarawa, Guadalcanal and Saipan were forbidden. Both RCTs were counterattacked during the night but this achieved little more than quickly depleting valuable troops Goto could not replace. Late the next day on 18 September, both RCTs were able to link up and push on to their respective objectives.

By the end of the third day, 19 September, the RCTs had cut the island in half, with two pockets of resistance. The main Japanese force to the northwest on Ramauldo Hill and the other dug in at the Green Beach defensive fortifications. After two days of harsh fighting and heavy casualties, the 321st had overrun the Green Beach defenses and the 400 dug in soldiers by flanking them from behind. At a cost of 300 casualties, the southern half of the island was declared secure. While the 321st was embattled to the south, the 322nd RCT moved across the island to the western coast securing the only inhabited area of the island, "Saipan Town", then swept north towards "Shrine Hill" and Romauldo Hill where the main 750-strong force was awaiting them, heavily dug in to the island's most formidable and difficult terrain. With the southern half of the island secured, on 23 September the 321st RCT was dispatched to nearby Peleliu, where the 1st Marine Division was taking massive casualties and nearing becoming combat ineffective as a unit. Securing the rest of Angaur fell to the 3,200 men of the 322nd RCT.

The Japanese defensive network on Romauldo Hill and the intense fighting that would take place there was in effect, a microcosm of the brutal fighting taking place in the Umurbrogol pocket on nearby Peleliu by the Marines, and later the 81st Infantry Division. The entire hill was honeycombed with interconnecting caves, pillboxes and bunkers built into the coral rock, forming an almost impregnable position where the defenders were dug in, determined to fight to the death and take as many American lives with them. Near the top of the hill was a small bowl-like valley with a lake surrounded by ridges almost 100 feet (30 m) tall, which became known as "the Bowl". To add to the defenders' advantage there was only one way into and out of the bowl, through a narrow gorge, later named "Bloody Gulch." As the 322nd RCT advanced on "the Bowl", they were met with withering machine gun, mortar and sniper fire, being stymied in their tracks.

From 20 September, the 322nd RCT repeatedly attacked the Bowl, but the dug in defenders repulsed them with artillery, mortars, grenades and machine guns, inflicting heavy losses. Gradually, hunger, thirst and American shellfire and bombing took their toll on the Japanese, and by 25 September, after three costly frontal attacks the Americans had penetrated the Bowl. Rather than fight for possession of the caves, they used bulldozers to seal the entrances. By 30 September the island was said to be secure although the Japanese still had about 300 more soldiers in the Bowl and surrounding areas that held out for almost four more weeks.[6]

Toward the end of the first week of October, the protracted conflict had degenerated into patrol action with sniping, ambushing, and extensive booby-trapping employed by both sides. Goto was killed on 19 October fighting to keep possession of a cave.[7] The last day of fighting was 22 October with a total of 36 days of fighting and blasting the Japanese resistance from their caves with explosives, tanks, artillery and flamethrowers. The 81st Infantry Division had finally taken the whole of Angaur, although at a high cost.[6]

The 322nd RCT sustained 80% of the American casualties on Angaur, with a 47% casualty rate. On Peleliu, men of the 321st and 323rd RCT's would go on to fight the remaining 3,600 Japanese defenders holding out in the Umurbrogal pocket for almost two months, often resorting to fierce hand to hand combat. There, another 282 men of the 81st Infantry Division would lose their lives with another 4,409 being wounded. Of all the casualties sustained by the 81st Wildcat Division in Operation Stalemate II, only about 52% would be fit enough to return to duty. A great number of American casualties were the result of head wounds inflicted by accurate Japanese sniper fire and their use of smokeless powder.

Aftermath

[edit]Airfields were being constructed as the battle was still being fought, but the delay in the start of the Palaus operation meant that the airfields were not ready in time for the start of the Philippines campaign in October 1944. Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr. had argued before the invasion of the Palaus that the operation was unnecessary, and military historians have agreed with him, suggesting that the main benefit was the combat experience gained by the 81st Infantry Division.

During the fighting, Seabees created an airstrip that would house B-24 Liberator bombers of the 494th Bombardment Group, 7th Air Force which engaged in frequent bombings of the Philippines and other Palau Islands.[8]

The 81st Infantry Division moved on directly to the battle on Peleliu to aid the 1st Marine Division, which had encountered extremely stiff resistance in the central highland of that island. They would remain on Peleliu for another month taking the island and mopping-up the remaining Japanese forces.

References

[edit]- Morison, Samuel Eliot (2001). Leyte, June 1944 - January 1945. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Vol. XII. Kent (Ohio): Castle Books. ISBN 0785813136.

- Smith, Robert Ross. The War in the Pacific: The Approach to the Philippines. The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II. Vol. III. Washington D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History.

- Moran, J.; Rottman, , G.L. (2002). Peleliu 1944. Oxford: Osprey Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1841765120.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c Moran & Rottman 2002, p. 89.

- ^ Moran & Rottman 2002, p. 13.

- ^ Moran & Rottman 2002, p. 39.

- ^ Moran & Rottman 2002, p. 21.

- ^ Moran & Rottman 2002, pp. 67–68.

- ^ a b Moran & Rottman 2002, pp. 70–71.

- ^ The HyperWar website here, on pages 178 and 179 describes it as "up until the night of the 19th" of October when Major Goto was killed.

- ^ Moran & Rottman 2002, p. 91.

External links

[edit]- The short film Action at Angaur (1945) is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.